How to Fix Your Gut, part 2

This week in part 2 we’re going to discuss the mechanics of digestion, absorption, fermentation and the role of fiber. These processes occur in the stomach, small intestine and colon and are co-dependent. For example, poor digestion because of high cortisol/low thyroid not only leads to malnutrition but SIBO. Fiber is a doubled-edged sword that can improve or worsen gut function so its important to know when to increase or decrease it. Let’s dive in….

TLDR:

1. Digestion occurs in the stomach and upper small intestine through mechanical and chemical breakdown. At the highest level, this is governed by energy availability and thyroid function.

2. Stomach acid, pancreatic enzymes and liver bile are the main tools of chemical digestion that occur in the stomach and upper small intestine.

3. Mostly the small intestine’s job is to absorb macro and micronutrients post-digestion. Optimal absorption is dependent on digestive function, villa health and intestinal permeability.

4. The colon’s job is to house the microbiome that ferments soluble fiber into short chain fatty acids that have both local and systemic effects. The typical assaults mentioned last week along with energy deficiency are responsible for dysbiosis that also have local and systemic effects.

Digestion is the first part of gut function and the goal is to breakdown food into a form it can be absorbed. Digestion begins with chewing along with saliva that contains amalyase, an enzyme that breaks down starches and lipase, an enzyme that breaks down fats. Chewing throughly and taking your time to enjoy the food masticates it into small enough quantities for the stomach to process and stimulates vagal tone. It also increases salivation which in turn increases amalyse and lipase.

Once swallowed stomach acid degrades the food further into something called chyme. Enough stomach acid and pepsin is particularly important for digesting protein. This is the first step in processing whole proteins into absorbable peptides and amino acids in the small intestine.

Low stomach acid is a risk factor for SIBO, protein and micronutrient malabsorption. GERD aka reflux is core contributor of SIBO.

Several micronutrients are required for proper stomach acid levels including B1, Zinc, Cl, and T3. Good vagal tone and low cortisol are critical too.

Chronically elevated cortisol is particularly damaging to digestion, gut barrier strength, immune response and microbiome composition.

Cortisol:

Lowers stomach acid

Lowers pancreatic enzyme release

Lowers bile acid secretion

Lowers secretory iga release

Increases intestinal permeability

Causes dysbiosis

Lowers active thyroid, T3

Inhibits the vagus nerve

The final and most significant stage of digestion occurs in the duodenum, the first segment of the small intestine. Here, the pancreas releases more amaylase and lipase to further breakdown starches and fats as well as proteases to further break down protein.

Here, the gallbladder releases bile into the duodenum to emulsify fats. Bile also plays an important antimicrobial role destroying pathogens as it flows down to the end of the ileum where is gets reabsorbed and recycled back into the liver through the portal vein.

Last week I mentioned lectins and in particular gluten as a potent irritant for some people. The most pathological state is know as celiac disease in which gliadin, a component of gluten (from wheat, barley and rye) inhibits Cholecystokinin (CCK). This in turn lowers pancreatic enzyme and bile release. This inhibition severely damages digestive function leading to malabsorption and malnutrition.

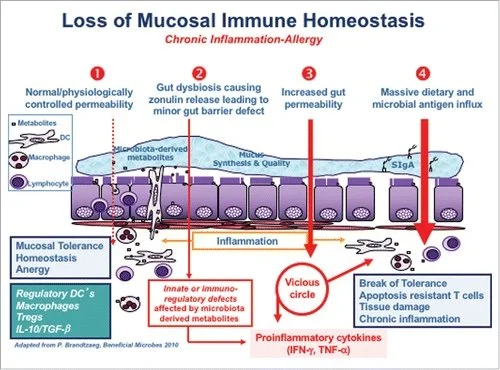

Another mechanism that can occur with both gliadin and reduced mucin layer is the release of zonulin. Zonulin is well-known to create intestinal permeability. In the case of a reduced mucin layer, bacteria are living directly on the gut lining which triggers zonulin release. In both cases, the leaky gut or the reduced mucin layer induces autoimmunity and a cascade of inflammatory reactions.

Maintaining the mucin layer is crucial for preventing leaky gut. Anything that leads to dysbiosis will do it. For example, consumption of antibiotics, pesticides, seed oils, and chronic stress will change the microbiome into a pathological state. Pathogenic bacteria will consume the mucin layer. Alternatively, if your microbiome is healthy but your diet lacks fiber the healthy bacteria can over consume the mucin layer. High fat, low fiber diets create a terrain for this situation.

As the digested food travels along the 21 feet of small intestine, carbohydrates, lipids and amino acids are absorbed through the villa either passively or actively. At this point, carbohydrates are already broken down into the monosaccharides (sugars) glucose, fructose and galactose, proteins into amino acids and peptides, and fats into fatty acids and monoglycerides.

Fat-soluble vitamins (A,D,E,K) are absorbed with the fatty acids, water soluble vitamins are directly absorbed and minerals through various mechanisms.

Since the small intestine should have low bacterial counts, very little to no fermentation of fiber should occur here. Fortunately, the small intestine has protective mechanisms to limit bacterial growth such as rapid transit time, the MMC (discussed last week), antimicrobial peptides, Secretory IgA (SIgA), the mucin layer, and a slightly acidic environment in the duodenum.

There are two kinds of fiber: soluble and insoluble that are both components of plants. Insoluble fiber’s function is pretty straight-forward, it stimulates motility and acts as a mechanical brush moving bacteria and undigested food down to the colon. Soluble fiber on the other hand is more complex. It turns into a non-absorbable gel that feeds bacteria. This process is called fermentation and should only occur in the colon.

As bacteria metabolize soluble fiber their poop becomes the short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) butyrate, acetate, propionate. Butyrate in particular feeds colonocytes. SCFAs also enter the bloodstream improving insulin sensitivity and glucose use as well as positively influencing autoimmunity.

As mentioned before if you don’t get enough fiber, the good bacteria will eat the mucin layer. However, most soluble fiber will indiscriminately feed both pathogens and probiotics alike. So if you have dysbiosis, eating fiber will WORSEN your gut problems but if you have eubiosis eating fiber will support your gut.

This is why so many dysbiotic people benefit from the carnivore diet. If you have severe gut problems, removing fiber, plant defense chemicals and PUFA (generally plant-based) will significantly lower LPS and gut-based inflammation improving your situation. It will also improve fatty liver as LPS is a core driver.

It’s important to realize eating carnivore, whether high protein or high fat, is an elimination diet and therefore a temporary patch until the gut is remediated. As discussed in my low carb article, without carbohydrates your stress system will get triggered. Proper cortisol management is critical to a healthy gut, slowed aging and decreased inflammation.

Reintroducing carbs after an elimination diet is both necessary and tricky. We’ll discuss that next week along with testing specific markers of digestive function and the microbiome.

Jonathan

This is for informational purposes only and should not replace professional medical advice. Consult with your physician or other health care professional if you have any concerns or questions about your health.